Profile

Sadegh Tabrizi is one of the few Iranian contemporary artists who have made a great contribution both to the “creation” and the “dissection” of Modern art in Iran. Therefore, it bears some significance to look at him from the “creation” point of view to be able to understand his pool of creativity, a perspective that encompasses both the artist and his art. This necessity has been spelled out through recent movements by some artists who, in establishing the foundations of their art, imitated and employed the roots of his style. In doing so, these artists have set off on the road to imitating what he had once practiced but no longer practices, or what he had skipped on his way to eminence.

Tabrizi can be considered a holistic artist with a multifaceted vision of reality who, in giving dimension to his practice, bestows new angles to Iranian contemporary art. This is so intensified that one cannot ignore a pervasive approach to indigenizing the Western Modern and Post-modern art through the Saqqakhaneh semi-school and the work of one of its central figures, Sadegh Tabrizi. He offered a series of “proposals” a few decades ago which, despite commonalities with other pioneers of theSaqqakhaneh School, surpassed them with a diverse series of experiments. Hence, he has played a vital role in dissecting contemporary intermediary art – a style that mixes Western and Iranian traditional art. Prerequisites of such a holistic approach can be traced in Tabrizi’s searching soul. Even before examining intermediary art at the Faculty of Decorative Arts, Tabrizi had built up a reputation for himself in traditional art and its vocabulary. Explorations in this apparently fantastic and experimental course assumed more serious aspects later when playing a significant role in the development of modern and contemporary Iranian art. What has been neglected to date is a complete catalog of Tabrizi’s work. So one has to resort to storytelling to be able to show his real art and to fathom the genesis of his artistic career.

Read More

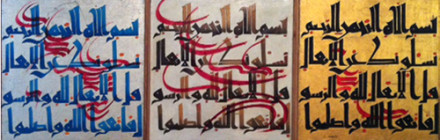

Upon graduating from three years of high school in miniature painting, and after employment in the ceramic workshop of the Administrative Office of Fine Arts in 1959, Sadegh Tabrizi chose to practice painting on pottery. This novel experience gave him an opportunity to work with glaze and fire. Unpredictable happenings and interactions were the most enjoyable moments in that work. The year 1959 was a very fateful year for Tabrizi’s artistic endeavors. While preparing inscriptions for a mosque, a tile worker by the name of Sanaee made Tabrizi realize how beautiful inscriptions were, and tempted him to make a free composition with letters and words. The result of this temptation was a ceramic panel (70 x 70 cm) that yielded a new composition in white and azure, the colors of inscriptions in mosques. The juxtaposition of letters neither expressed a concept nor produced an expression. This delightful experience encouraged the artist to employ the same technique in painting on jugs, bowls, and plates using ochre and brown colors on a cream background, and azure and turquoise on a white background. The significance of this ostensibly minor incident and its continuation led to numerous arguments about the emergence of calligraphy in Iranian contemporary art. In fact, it can be said that the trend known as “calligraphy-based painting,” which later emerged in the work of Saqqakhaneh painters and again in the work of calligraphers (from a different perspective and through calligraphy-based painting), originated from Tabrizi’s innovative practice. This can be substantiated by the works and written documents of the time that point to the quality of this movement. Therefore, this incidental stance of the artist toward calligraphy and its visual and non-verbal qualities can be considered the first period of his artistic career. The term “incidental” points to the fact that in the second half of the 20th century, Western art, which was joined with some delay by Iranian contemporary art, has often incorporated incidents rather than following a school-based approach.

Upon the inauguration in 1960 of the Faculty of Decorative Arts, which was established to offer complementary courses for high school graduates in arts from Tehran, Tabriz, and Isfahan, Tabrizi joined the students and found himself in the same course along with Mansour Ghandriz, Faramarz Pilaram, Massoud Arabshahi, and Hossein Zenderoudi. This new environment had an extensive library that provided students with a rare opportunity to conduct research on past and present Iranian and world art, and to avoid repetition of ideas in their practice. Here, this small group of students devised a sort of intermediary art, which observes principles of modern Western art while employing traditional elements from Iranian art.

Tabrizi and Arabshahi held a joint exhibition of their ceramic works in 1961 at the France Club. Hossein Kazemi, who had returned from Europe and was running the Tabriz School of Arts, simultaneously held an exhibition of his Dadaist ceramic work at Farhang Auditorium. The difference between these two exhibitions was the Iranian atmosphere in the former, something Kazemi admits to in all modesty. Tabriziexpanded the domain of his explorations and, using traditional Iranian motifs and techniques, created numerous works in fresh forms. These techniques included tile work, engraving, book illustration, plaster work, collage, painting on old inscriptions, painting on glass, use of mirrors in painting, and use of padlocks, chains, and various objects. These techniques are examples of proposals that the artists offered to the Iranian contemporary art world. Tabrizi made a juxtaposition of his personal documents – including school workbooks, identification notebook, school identification cards, certificates, bank notebooks, athletic club cards, and university entrance exam card – on a panel within a composition decorated with sealing wax and the common inscriptions found on documents and seals. Entitled Life Workbook, the work was displayed along with other works inspired by spells and the illustrated pages of books that were shown along with Massoud Arabshahi’s relief works at the Faculty of Fine Arts of Tehran University in 1964. Life Workbook can be considered a proposition for “conceptual art,” but this was not what Tabrizi intended.

Tabrizi graduated from university in 1964, and decided to continue for a Master’s degree along with Ghandriz, Pilaram, and Arabshahi. Top students of the Faculty of Fine Arts, including Morteza Momayez, Rouyin Pakbaz, Hadi Hazaveyee, Sirous Malek, and Mohammad Mahalati, who would be considered an opposite camp to the students of the Faculty of Decorative Arts, established a gallery along with Tabrizi,Pilaram, Arabshahi, and Ghandriz. This effort had been previously made by others, but had never succeeded. This group of thirteen artists succeeded in gathering many avant-garde artists together at the Iran Auditorium, and in organizing the first well-received exhibition. Activities at the Iran Auditorium reached a point where artists that included Sohrab Sepehri, Bijan Safāri, Marcos Grigorian, Parviz Tanavoli, andManochehr Sheibani, were invited to hold a group exhibition at the Saderat Bank building in Jomhouri St. Tabrizi’s work was received especially warmly in the first exhibition by spectators and collectors. He says, “The gathering at the Iran Auditorium would not have been possible if it had not been for Momayez, and their four-member group would have never joined the students at Tehran Universitywithout Ghandriz.”

Although Ghandriz tried hard to save the infant he had given birth to, the group disintegrated after the first exhibition at the Iran Auditorium due to disagreements and disunity. He persistently continued his work there, but his death put an end to this effort. Upon dispersal of the group, some members quit painting to practice graphic design, architecture, and research in art history. Arabshahi, Pilaram, andTabrizi, however, continued painting. Tabrizi’s paintings in the inauguration of the Iran Auditorium are reminiscent of miniature paintings in old books that have been embellished with abstract expressionist lines in black and presented on tanned hide. Azure, white, gold, orange and turquoise spots can be detected in these compositions, and calligraphic lines can be discovered through meticulous observation. This second period of Tabrizi’s artistic endeavor is presented in a second group exhibition. The third period of his creativity includes collages that are presented in an exhibition with Massoud Arabshahi at Tehran University. These four artists – Tabrizi, Pilaram, Ghandriz, and Arabshahi – were founders of the first Office of Interior Design in Iran, which was established in 1964 and eventually broke up when Ghandriz died in 1965.

Another one of Tabrizi’s experiments, a review of ancient Iranian arts, was made in 1963. Copper engraving and the incorporation of antique stones and coins on these engravings mark the fourth period of his artistic experimentation.

Tabrizi did not veer far from his original vision during this period, and other periods of his career. These periods have their roots in a single perspective – the depth and structure of which is a fertile area of investigation. He created plaster relief work on panels in the fifth period of his artistic career.

If we are to assume a sixth period for the artistic endeavors of Tabrizi, it includes works on pages of old books and inscriptions that sometimes take the form of written prayers and lead to collage elements that appear in the background of paintings. Moving to another period, we see that Tabrizi has only a few works of stained glass using mirror instead of color on a black background. We can find this style – use of mirror in painting – in the glass arts of the Qajar period. This period of his work can be considered transitory and marked by proposals.

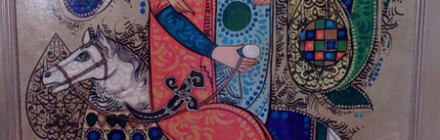

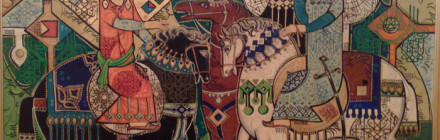

Tabrizi employs miniature painting techniques and incorporates Persian and religious motifs in large-scale paintings which are warmly received by the public. These paintings feature pure gold, orange, azure, turquoise, green, and other colors along with black complementary lines. Large-scale works of this kind were mounted on the walls of Nour Auditorium at the Hilton Hotel in 1969 to celebrate 2500 years of Persian history. These works can be considered to constitute the eighth period ofTabrizi’s work. They are mostly images of riders on calm horses facing each other, or of lovers found in Persian paintings re-cast in a fresh form in his work.

Although these works were leisurely produced through different periods, they have paved the way for the most intense period of Tabrizi’s career in terms of innovation and quality beginning in 1970. Instead of saturating his work with illumination and page decoration, Tabrizi hints at Persian miniature painting by using inscriptions in the form of broken Nasta’liq to fill the negative space of the paintings. Here he realizes an important innovation that calligraphy can create abstract forms in free compositions. Looking at the suspended calligraphy-based motifs of previous works,Tabrizi comes up with the idea of an abstract use of them in individual compositions. This is perhaps the most successful period of his career. Inspired by calligraphy, especially broken Nasta’liq as an abstract form on hide in black ink, Tabrizi produces a large number of works. He adopts this approach to reach at a seemingly easy method in painting, which is inspired by Persian calligraphy but goes beyond that to reveal itself as a completely abstract and expressive form. Works of this ninth period of Tabrizi’s career were exhibited during a solo exhibition first in 1970 at Burgese Gallery and then at Sirous Gallery in Paris. Interestingly, the artist uses the same style, which has unlimited variation, in large-scale works on rawhide, canvas, and paper that are exhibited in Australia and East Asian countries. This period of Tabrizi’s work can be considered the result of his diverse research and experimentation into both Persian and Western methods and representation. He later transformed this exploration into an “Abstract Expressionism” that displays a graceful fluidity of mind, and possesses the same fundamental characteristics that are unique to modern Western art.

For information about this artist and purchase availability please contact Shirazi Art Gallery.